I’d played more than a hundred football, basketball, and baseball games between seventh grade and high school graduation, but my mother had never seen me play. Not until the night we played Livingston a second time, this time on our home floor. I was excited, knowing she’d be there, but I was a bit nervous, too. I hoped I’d do okay.

Those were hard times for a divorcee, a single woman with two children. With no social service assistance, my mother worked night and day to make life as comfortable as possible for me and my sister. Finances had improved now that she’d acquired a country school teaching position, but she still had to work from early morning to late into the night—correcting papers and preparing the next day’s lessons for fifteen or more students. Because no copy machines were available, worksheets had to be hand-printed, one at a time.

Mother didn’t know anything about basketball, football, or baseball. And she didn’t much care to know. She’d been raised in a farm family where work was a necessity and school games were thought to be a frivolous use of time. What’s more, her sisters had married farmers, and their husbands had the same attitude towards sports. At a time when life was so hard for Mother, they probably thought I should be home helping rather than staying after school each night to practice football, basketball, or baseball.

But they never criticized or said a word about it to me. And Mother didn’t either. She came home from school

, changed into her work clothing, prepared the supper, then cleaned up the kitchen and did dishes after supper. She then worked late into the night correcting papers and preparing lessons for the next day. All the while, I played games before supper and worked on my lessons afterwards. Mother seemed happy about that. She had dreams for my future. She worked hard so I could enjoy the present and secure the future.

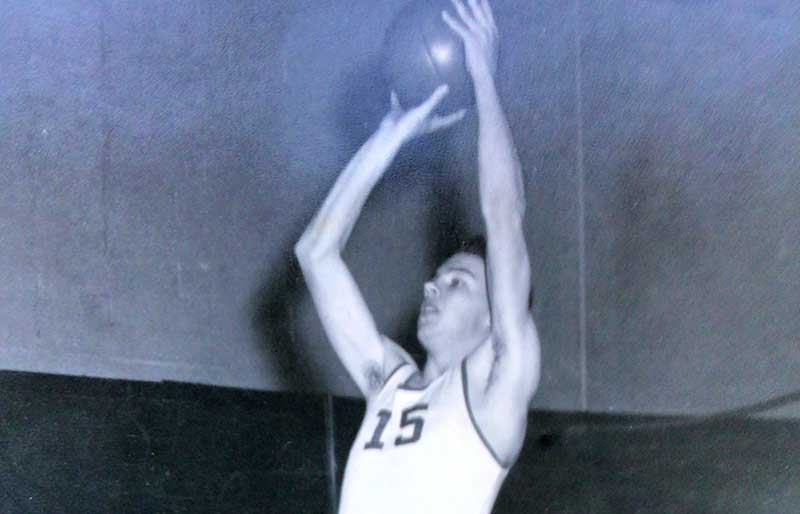

But she’d found time to come to my basketball game that night. I played for Barneveld High School. Our opponent, Livingston, was a very good team. We’d played them before on their home court, and we’d lost. I’d scored eleven points, my lowest production of the season. Would tonight be different? I hoped so.

We forged ahead early in the game and never relinquished the lead. It seemed that my every shot was making its way into the net. Four and a half minutes remained in the game, and we were ahead by eight points. That’s when I dribbled the ball up the floor, stopped about twenty feet from the basket, elevated into my jump shot, and launched the ball into the net once more. But this time, I came down too close to my defender, and the ref called a fifth foul. I walked off the floor to the crowd’s standing ovation, grabbed my warm-up jacket, and sat on the bench to watch the last four minutes as Barneveld proceeded to win the game. I didn’t know it at the time I left the court, but I’d scored forty-five points, four points short of the league record of forty-nine. I’d probably have been disappointed if I’d known that I fouled out when two more baskets would have equaled the league record. But by the time I found out, it didn’t matter.

Mother had waited and approached me as I, now dressed in street clothes, exited the locker room. She said, “Everything you tossed in the air fell into the basket,” as if I had little to do with that result. She probably thought that gravity played a bigger role in the outcome than I did. But then she said, “I was overcome with pride when everyone stood, clapped, and cheered. I’m so glad that I finally got to see you play.”

Mother knew little about basketball, but she knew appreciation when she heard it. And to see her son appreciated that night thrilled her more than forty-five points could ever have done. I might have been disappointed by not achieving a league record, but I understood that my mother couldn’t have experienced her thrill that night if I hadn’t fouled out early. If I’d have played the game to the end and walked off the floor with my teammates, there’d have been no opportunity for an audience’s show of appreciation, and Mother wouldn’t have experienced her thrill: watching everyone stand, clap, and cheer for her son. Even then, I knew that I’d achieved a bigger victory than scoring points and winning a kid’s game.