December 7, 1941: B-17 C (Flying Fortress) my wife’s uncle, pilot Earl Cooper, flying in darkness and low on fuel, approached Pearl Harbor. He intended to land at Hickham Field for refueling before continuing on to Clark Field in the Philippines.

As dawn broke and they approached the islands from the east, Earl’s navigator spotted what he thought were islands in the distance, islands that weren’t supposed to be there. His navigator said that those islands must be clouds. About then, Earl’s backside gunners reported a large formation of airplanes about ten miles to the north. At first, they thought they were friendly aircraft, but when fighter planes, the rising sun painted on their sides, sped toward them with guns blazing, Earl knew it was time to vamoose. He dove toward the water, all the while hearing bullets thump against and through the skin of his big helpless plane.

When he rounded Diamond Head at about three hundred feet, he saw ships burning and destruction all around. His fuel gauge registered empty. American anti-aircraft fire pelted his plane from below while Japanese Zeros attacked from above. His number four engine was disabled. He ordered his men to prepare their parachutes, but what chance did they have this close to the ground?

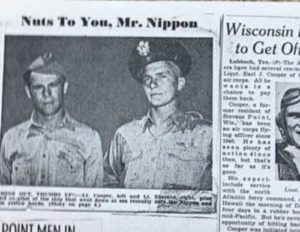

Earl Cooper

I spent one evening with Earl telling me about his WWII adventures. I have a file stuffed with news articles that describe his heroics. I have a book that describes him as a “Living Legend.” And I have two large wall pictures, one showing and describing his entrance into that infamous attack on Pearl Harbor; the other showing his rescue at sea. I knew that I had to tell this man’s story—tell the story of one man’s contribution to the most significant period of the 20th century.

Earl Cooper was born and raised in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, the son of a railroad worker. He had a younger brother, Bill, and two younger sisters, Evelyn (Weinkauf) and Isabelle (Larson). Earl was renowned as a fine athlete, an all-conference quarterback for the Stevens Point Panthers. After graduation from high school, Earl attended the local college, but with war raging in Europe, he anticipated that America would soon be involved, so he joined the Army Air Corps in 1940.

After training in Texas, he ferried bombers to England to help Great Britain’s war effort against Germany. On one of these missions, he ferried President Roosevelt’s son Elliot across “the pond.” Living up to the reputation of many WWII flyers, Earl was a bit of a renegade. Once, while on a training mission, he diverted his plane to buzz his parent’s house in Stevens Point.

Earl thrived on excitement, but he never expected the chaos he’d fly into that fateful day, December 7, 1941. He’d just ordered his men to prepare their parachutes, when, at the last minute, he saw an opening at an alternative site, Wheeler Field. He brought his big bird straight down for a belly landing, sliding to a stop just short of a squadron of P-40s. His men hastily exited the B-17 and raced for cover, not a one injured or killed. Although he didn’t know it, this wouldn’t be the only time that he and his crew would live through a potentially treacherous exit from their plane.

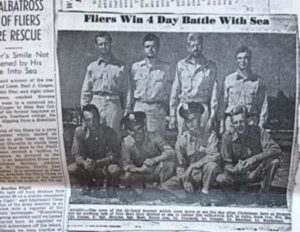

Less than three weeks later, on December 26, Earl piloted his B17 on a patrol west of the islands, watching for the enemy’s return. Somehow, he was given the wrong coordinates and was directed too far away from the islands, and he ran out of fuel five hundred miles from Hawaii. Although no bullets slammed into him this time, he performed a dead-stick landing, an extremely difficult maneuver when landing on the sea. He feathered his props, turned his blades into the wind, and told his crew to prepare for the crash. His B17 was no seaplane—it was more like a 48,500-pound rock. But he didn’t crash. He brought his plane down, landing as light as a feather on that sea. Once more, he’d brought his megalith down without loss or injury to himself or his eight crew members.

They were stranded in two life rafts on the vast ocean. They first checked their provisions—two canteens of three-week-old coffee, a wet package of cigarettes, and amongst the nine of them, a little more than six hundred dollars—six hundred dollars to spend and no where to spend it.

Earl knew the home base would send search planes, and they did hear planes in the distance during the next couple days. They launched flares to attract attention, but to no avail. Then—the skies were empty. The second night out, sharks circled their rafts until dawn. Two severe storms caused them to drift hundreds of miles further out. They shot an Albatross with a .45 pistol and then ate the bird raw. They also ate the fish they found in its stomach—not exactly sushi—but that was the last of their feasting.

By their fourth day at sea, they were mighty hungry and losing hope. They hadn’t heard a plane for the last two days. The ocean was angry that day, spewing waves up to forty feet high. Earl’s crew was becoming desperate. How much longer could they last? Unbeknownst to Earl, the Army had listed him and his crew as missing in action and had notified his parents that he was lost at sea.

They were at low ebb when a miracle happened. They heard a plane engine overhead, and looking up, they saw a flying boat, a plane that could land on the ocean. But could it land with waves forty feet high? The sea was far angrier than any sane pilot would consider for a landing. But the pilot banked his plane and came down in those heavy seas, a heroic act that saved Earl and his crew and brought the PBY pilot, Ensign Frank M. Fisler, the Navy Cross for his bravery.

Squadron Commander, Major Earl Cooper, now flying a B-24, #214 the Dogpatch Express, continued to fly missions throughout the Pacific theatre. His numerous actions and heroics were described in the book, “Finish Forty and Home,” by Phil Scearce, 2011, University of North Texas Press. When writing about his war heroics, Scearce described Earl as “an Air Corps living legend” (p.174).

Earl eventually came home to Stevens Point, where he established a Standard Oil station and a bulk and heating oil distribution business. After his death, Earl’s sons, Jim and Don, and their wives, Kay and Kathy, continued operating the businesses. It’s now owned and operated by Jim’s son, William Cooper.

Those life rafts that sustained Earl and his crew during those dismal days at sea found happier times after Earl returned home. My wife, Lynn Weinkauf-Thorpe, often reminisces about the enjoyable days that she, her sister, and their cousins had when visiting her grandparents’ cabin near Amherst Junction. They spent many happy hours paddling her uncle’s rafts on Lake Emily.