By Harold William Thorpe—author of The O’Shaughnessy Chronicles, a farm family’s epic four-book history.

I learned life’s most important lessons from family farmers.

The farmers I knew best were family members, but those I extol here could be any family-farmer. I describe their sense of decency, their positive attitudes toward work, their working together as a close-knit family unit, their can-do attitude, and their helping relatives, too.

Many non-farm families have similar qualities, but I doubt that they so universally adopt these practices as do farm family members who live, work, and play together twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

Farming isn’t an occupation for these farm families; it’s a way of life.

The farmers’ attachment to their land is a connection that those who’ve never farmed can’t possibly appreciate. Perhaps it harkens back to the time when peasants couldn’t own land so migrated to America—where from a distance they saw possibilities. They took on the hardships of travelling thousands of miles and leaving their homeland to realize a dream and become lords of their own land, frequently a 160 acre homestead.

Perhaps they thought like Gerald O’Hara, Scarlett’s father in Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel Gone with the Wind, who said to Scarlett, “Land is the only thing in the world worth workin’ for, worth fightin’ for, worth dyin’ for . . .”

The family-farmer (and his family), have, in general, a different set of standards then the businessmen and politicians who are condemned in the headlines today. A family-farmer is a businessman, yet their values are generally at a completely different and more humane level than those who make the newscasts. Businessmen and politicians who too often consider themselves superior because they received an elite education and have higher incomes (even though their practices may be cutthroat) do not have the distinction of achieving society’s most important function; feeding its people.

The family-farmer knows it’s better to care for their animals than to abuse or mistreat them. And many farm youth learn humane animal care through their membership in the National FFA (Future Farmers of America) organization.

They also experience personal growth and learn leadership skills through this agricultural education. Numerous farm youth are members of 4H, where, in addition to animal care, they learn to bake, sew, and grow the most productive fruits and vegetables.

Family-farmers are smart a practical way. All those I knew were carpenters, mechanics, welders, electricians, plumbers, and sometimes veterinarians. They tracked the Chicago livestock markets as closely as the daily weather report. They worked side-by-side with their family, and the children knew exactly what it took to produce their next meal. And few, if any, blamed the boss when things went wrong. Instead, they set out to make the repair.

I met an executive of a printing company that had opened a printing plant in Southwest Wisconsin. He said because the farmer boys they hired had no prior printing experience some of their company’s executives thought the new plant location was a mistake. The man told me, “Those farm boys are the best workers we have in any of our plants. When there’s an equipment breakdown, instead of waiting for a repairman to show up, they wade in and fix the problem.”

Family-farmer friends, Dave and Marilyn Wiesner, who live outside Winneconne, Wisconsin, have taken many trips to Europe, especially to Austria and Switzerland where they’ve become friends with several farm families. Dave told me, “When their equipment breaks down they head for home to wait for the repairman to show up.” They don’t consider repair to be their responsibility, nor do they have the skills to do the job.

Dave said that more than once he’s crawled under one of their hay balers to do a minor repair they’d never think of doing.

As part of the introduction to my book, America’s Small Town Heroes, I wrote, “At first farmers and ranchers populated small rural towns, and they quite naturally relied upon their neighbors. It was necessary for survival. For generations they depended on each other – to help construct buildings, with the harvest or for solace when calamity struck.”

Sadly, the family-farm has steadily eroded from America’s landscape over the last two hundred years.

Farmers composed 90% of the labor force in 1790, 58% in 1860, 38% in 1900, 18% in 1940, and by 1990, only 2.6% were left on the land1. As the family-farm slips away we lose more than an economic institution. I believe we’ve also lost much of the underpinning that’s held family and communities together.

Farm families lived, worked, and prayed together, and helped neighbors whenever there was need. This closeness with family and neighbors produced cohesive units that learned to live together through good times and bad. I believe this steady erosion of family-farmers has also produced an erosion of the values they lived by.

Celebrating My Farm Family

From kindergarten through a doctorate degree I’ve completed more than twenty years of formal education. Those hundreds of classroom hours allowed me to earn a living throughout my adult years. But along the way I experienced a different kind of education that influenced my life more than those formal classroom hours and laid the groundwork for my writing career.

Although I don’t remember my first farm days, they began when Mother and Dad came to live on Grandpa and Grandma Fitzsimons’ farm, located a few miles northeast of Mineral Point, Wisconsin on Antoine Road, currently the Dave Lawinger farm.

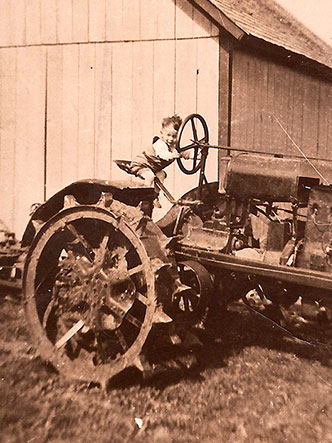

Pictures indicate that Grandpa tried to make me a farmer by the time I celebrated my first birthday.

After Grandpa Fitzsimons died when I was sixteen months old we lived in Wisconsin, California, and several points in between before settling permanently, when I was seven years old, near my Wisconsin farmer aunts and uncles. My most vivid memories of those years are the times I visited the three farms of my uncles living in the area.

Although I wasn’t conscious of it at the time I was gaining a lifetime impression about the life of a farm-family. They worked long hours doing field work and caring for their animals. The farmer could repair anything from a thrashing machine to a child’s toy airplane.

But best of all they were kind, generous, and helpful men and women.

Uncle Amanza Powell, who lived southeast of Dodgeville on Brennan Road, would take time from his fields to tease and play with me, my sister, and my younger cousin. Uncle Amanza knew when the willow branches contained enough sap to allow him to turn them into skillfully crafted whistles for his young nephew’s pleasure. He made the best sounding willow whistles you can imagine, and when my sister or cousin complained because they didn’t have one, he’d cut more twigs and make a second and third one, too.

I learned that the sweetest sounds come from an instrument carved by someone who cares enough to make it just for you.

Uncle Earl Paull, who lived two miles east of Ridgeway beside Hwy 151, would tell us stories and dance a jig or play spoons while Aunt Anne belted out a song on the piano. And on Saturday nights he’d drive to town to buy a sack of ice-cream pints that he’d cut in half and we’d each choose a flavor and select our half pint—a rare treat for this admiring young nephew.

Aunt Ruby and my mother’s brother, Uncle Mort, lived on a large family farm that was seventy miles away. They would host family members each summer and take us fishing at their cabin on the Rock River near Janesville. And their daughters, Dolores and Phyllis, who were quite a bit older than me and my sister, would entertain us with horseback rides and gardening lessons.

I learned that these were kind, considerate, and honest men and women. Not only did they do their best to entertain family, but I watched them show the same generosity of spirit when giving help to a stranded motorist. They didn’t just let the strangers use their phone, they did the actual repair work when they could and shared their food. They gave gas and gas cans, as well. And more often than not, the gas wasn’t paid for and the cans weren’t returned.

But they never stopped helping.

I think these early experiences with my farmer relatives influenced my personality and attitudes more than those years of formal education. And undoubtedly, those experiences were the foundation for my O’Shaughnessy Chronicles novels – not so much that I had farm experiences that fed the content of my books, but more-so that I felt indebted to tell the story about those family-farmers who influenced me so completely.

I went to live with Chuck and Dorothy Tredinnick, as a farm laborer, during the 14th and 15th summers of my life. Their farm was northeast of Mineral Point, out toward Jonesdale. Dorothy’s father, John Fitzsimons, was a cousin to my grandfather, Will Fitzsimons.

Although I’d watched from afar as my uncles and cousins worked, I now learned firsthand that a farmer’s life is different than playing cowboys and Indians in the hayloft, cutting whistles from willow trees, or ice cream pints on Saturday nights. I was about to become acquainted with the workday of a farmer.

When I arrived at their farm on the Monday after school was out, one of my first jobs was to cultivate corn. I wasn’t old enough for a driver’s license, but I was chomping at the bit to drive a car, and that International H tractor became my International racecar. Chuck probably made a mistake when he showed me how to lock down one wheel by disconnecting the flange that secures both brakes.

With the ability to stop one wheel completely I could turn that Model H formula racecar on a dime. And I used that brake fully, never slowing down at the end of a row, rather spinning the tractor like a top and heading down the next row far ahead of my competition. I may have won the race, and maybe established a record time cultivating a cornfield, but Chuck must have pulled his hair out when at the end of each day we searched the field for cultivator sweeps that detached and I’d left far behind.

He never got angry, never screamed or hollered, but he made sure that I did most of the searching. Chuck knew that was a lesson I needed to learn—those who create the problem must fix the problem.

I learned to start an old Model A Ford, made into a truck, by rolling downhill and popping the clutch; to swing a scythe at tall thistles; to stack bales higher than my head on a moving wagon; and to stack grain bundles into a shock, then later pitch those bundles into the maw of a thrashing machine that complained so loudly and shuddered so violently that you’d think it was a midwinter harvest. I learned to swing a pitchfork far better than I ever learned, or cared to learn, how to swing that scythe.

We worked with neighbors, all distant Fitzsimons cousins that I was meeting for the first time. I learned to enjoy and appreciate them as they guided and entertained me while moving from field to field. As we moved our harvest from one farm to another each wife of that farmer provided the noon-hour meal, and each did her best to outdo the others, all providing food fit for a king.

I loved those days in the fields with these kindly and helpful relatives.

I was never fond of the early morning and late night milking when I was so tired that I could barely resist joining the calves on their straw beds. But when I was ready to collapse, Chuck reminded me that milk is the spigot that turns out the cash that allowed him to employ me. Through it all, Chuck and Dorothy were kind and patient with this bumbling, small-town lad.

These were men and women I learned to respect and adore. It took me a while to internalize it, but these aunts, uncles, and cousins laid the foundation for how I came to believe a caring person should behave.

As I reflected on these memories, I was also inspired to also write 15 Life Lessons I Learned from Family Farmers. Enjoy!

Footnote:

- Spielmaker, D. M. (2018, March 21) Growing a Nation Historical Timeline. Retrieved from https://www.agclassroom.org/gan/timeline/index.htm