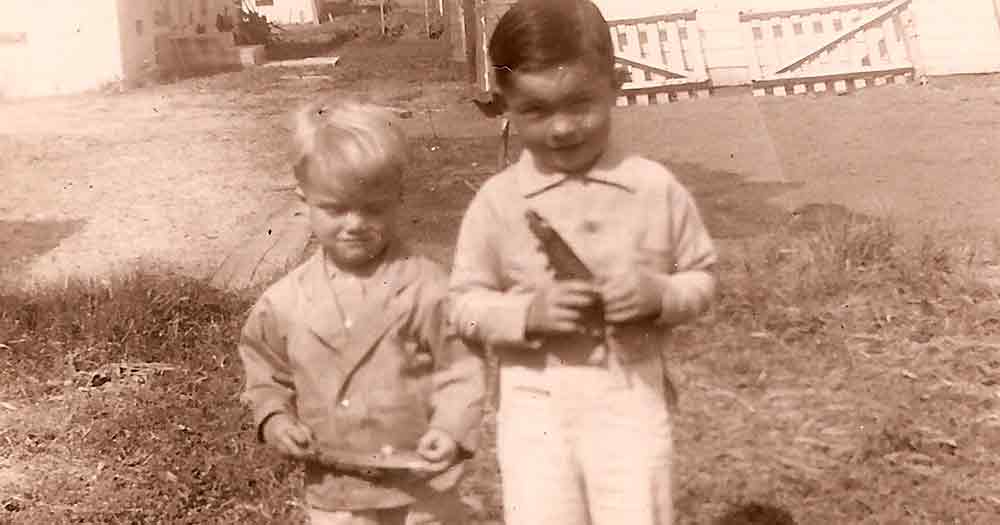

When I was four years old, my best friend was Binny.

His name probably wasn’t Binny, but I couldn’t say his name right, so he was always Binny to me. He lived next door, so we often played together. We’d ride our tricycles, play in the backyard with our trucks, and sail our little boats down the street’s gutter when neighbors watered their lawns and a thin stream of water flowed freely. Our plastic boats were small, so it didn’t take much to float them.

Our backyard was fenced to restrain our terrorist goat, Jack. We named him Jackrabbit because he could jump higher than a rabbit, but we called him Jack. When he first arrived, he’d slip out of the shed and raise havoc in the neighborhood. The fenced yard kept him contained—most of the time—but a goat in the backyard posed a problem for Mother. After washing our clothes every Monday, she’d hang them on the line to dry. And that clothesline was in the backyard. There shouldn’t have been a problem because Dad or Mother secured Jack in the shed when clothes were on the line.

Our backyard was fenced to restrain our terrorist goat, Jack. We named him Jackrabbit because he could jump higher than a rabbit, but we called him Jack. When he first arrived, he’d slip out of the shed and raise havoc in the neighborhood. The fenced yard kept him contained—most of the time—but a goat in the backyard posed a problem for Mother. After washing our clothes every Monday, she’d hang them on the line to dry. And that clothesline was in the backyard. There shouldn’t have been a problem because Dad or Mother secured Jack in the shed when clothes were on the line.

But Jack must have carried a calendar because he always knew when Monday arrived. And I swear there wasn’t a latch in town that could stop Jack when he was determined to get at those clothes. He always found a way out. He’d slip through a space that you’d think your cat couldn’t get through. Or he’d jimmy the latch and push the door open. After the door was better secured, he pushed his way through an open window to escape the shed and get into the yard.

Finally, Mother decided to station guards to watch for Jack’s escape, and can you guess who those guards were? Why, they were Binny and me. We could play as usual, but on Monday we were cautioned to stay close and keep an eye out for Jack. Our neighbors had complained that Jack ate clothes off their lines. I never saw Jack eat clothes, although I’d seen him nibble on them a few times. Sometimes when he felt rambunctious, he’d yank a pair of pants or shirt off the line and drag it through the dirt.

I wish I could tell you that Binny and I were good at our jobs, but that would be a big white fib. We’d start playing and forget about Jack, and, too often, Mother would have to do the wash over on Tuesday. It’s a good thing that we weren’t getting paid for our work, because I think we’d have forfeited the money about as fast as we earned it. We promised Mother that we’d do better, but she must have doubted our word. We never actually got fired, but we did lose our job. One Monday, Jack raided the line again. Jack disappeared the next day, and we never heard from him again.

I didn’t mind much. Watching out for him put a crimp in our play—especially when we wanted to leave the backyard for the front and sail boats down the gutter.