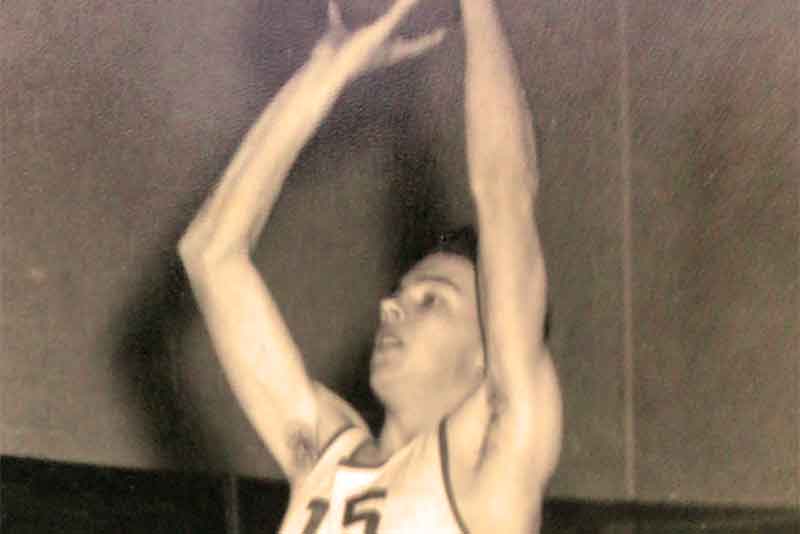

I was known as a shooter during my senior year of basketball. When I had a slight opening, I drove to the basket. When I didn’t have an opening, I worked hard to create one. But it wasn’t always that way. I’ll never forget that night on the court when shooting the ball was worse than embarrassing; it was humiliating.

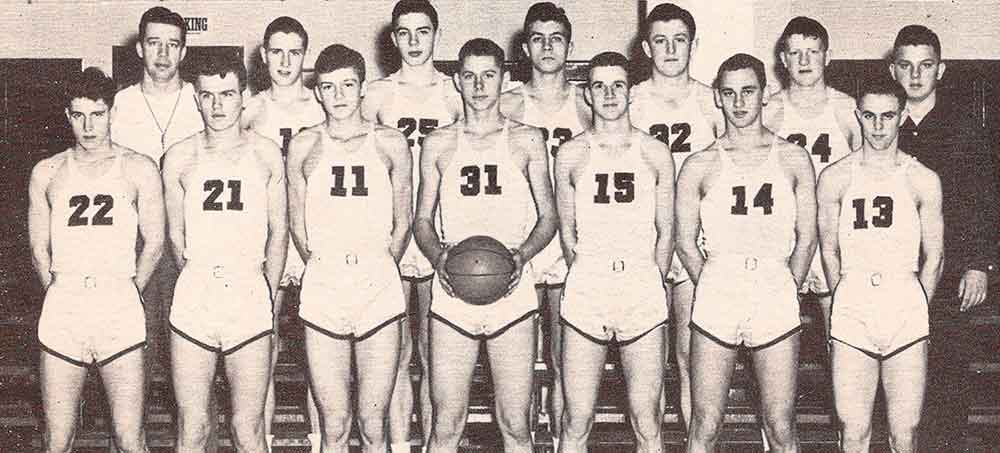

I scored fifteen points in my first high school game—one free throw and seven baskets from near what we now call the three-point line. We didn’t have three-point shots back then, so each of my baskets counted two points. Mineral Point Coach McKenzie was impressed enough to move me from the B team to the A team—what we now call varsity.

I immediately became a starter on the A team. No coach brings up a freshman kid with potential up to sit on the bench. I was young, just a month beyond my fourteenth birthday, and I was now playing with juniors and seniors, all of them two to four years older than me.

I was so intimidated that I stopped shooting the ball. Fortunately, I handled the ball fairly well, was a good defensive player, and was tall enough to get some rebounds, so I added some value to the team. But instead of shooting, I’d always pass.

During practice, whenever I had an opening, Coach would holler, “Shoot, Skip! Shoot the ball!” With enough urging, I’d shoot during practice, but I still wouldn’t shoot in the games. This continued throughout the early part of the season. Coach had urged me to shoot dozens of times before that fateful night on the court.

It was a close game at halftime, and we’d only been a few minutes into the second half when it happened. The opponent had scored, and after receiving the out-of-bounds pass, I’d begun to dribble up the floor toward our basket. I wasn’t to the center line yet when I heard this voice boom from the sidelines: “Shoot the damn ball.”

It was a close game at halftime, and we’d only been a few minutes into the second half when it happened. The opponent had scored, and after receiving the out-of-bounds pass, I’d begun to dribble up the floor toward our basket. I wasn’t to the center line yet when I heard this voice boom from the sidelines: “Shoot the damn ball.”

Like Pavlov’s dog responding to the bell, I responded to Coach’s demand.

I shot the damn ball.

But being so far away from the basket, it fell far short. I heard a pronounced gasp, and a few boos emerged from the crowd.

Coach called a timeout and, with reasonable calm, asked, “What’d you do that for, Skip?”

Perplexed, I said, “You told me to.”

“I didn’t tell you to shoot, not that far from the basket.”

Apparently, I heard the call of someone in the crowd, undoubtedly a fan of the opposition. Unbeknown, he struck at my weakness, my indecision about shooting the ball. Because I wouldn’t shoot, Coach conditioned me to shoot on cue. And I heard the cue in the gym that night.

I’m sure that experience slowed my shooting progress for a while, but it didn’t permanently disable me. I led the league in scoring from the floor when I was a senior. There were eight teams in our league, but we refused to play ourselves, so we played seven teams twice—fourteen games in all.

But you know, none of my successful games remain as vivid in my mind as that night I imitated Pavlov’s dog.