My four books present the O’Shaughnessy family story, a life progression similar to what many families experienced during those difficult 20th century years. Families struggled to overcome obstacles that most people living today can only know through reading books. I could never have begun or completed this writing venture if my mother hadn’t given so much of herself, steering me down a path that led to this outcome.

My mother, Laura Annette Fitzsimons, is the inspiration for Catherine O’Shaughnessy.

Catherine is the youngest of the three O’Shaughnessy sisters. She makes her appearance in Giddyap Tin Lizzie, shares center stage with Sharon and Ruby in Bittersweet Harvest and Puppet on a String, and, her sisters now departed, she becomes a one-person-show in the last O’Shaughnessy book, Strawberry Summer.

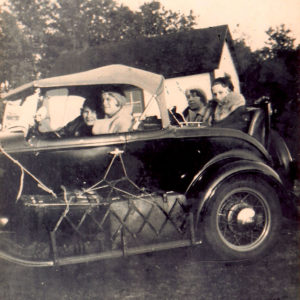

Mother was born in Mineral Point, Wisconsin on August 22, 1906. She was named after her father’s sisters, her Aunt Laura and Aunt Annette (Net). When asked her name as a child, she’d respond, “Laura Aunt Net.”

She was born in a large ten-room house that her father, Will, purchased from the priest at the German Catholic Church. It had been the church’s schoolhouse and was now being replaced. After Will purchased the schoolhouse the priest wouldn’t give him the right-of-way to move it off the land.

The story goes that Will visited the priest with a pint of whiskey. Before long they exited the parish house arm-in-arm, the best of friends. A few days later, Will and companions moved that big house one-half mile with horses pulling it uphill to its resting place at the top. I reconstruct in grand detail this horse-drawn house moving in the first O’Shaughnessy book, Giddyap Tin Lizzie.

Mother attended school in Mineral Point into the beginning of 7th Grade. She had started kindergarten a year late because she was bedridden for months, almost dying from a burst appendix. I recreate this near tragedy when little Catherine almost dies from a burst appendix in Giddyap Tin Lizzie.

When her family moved to a farm on the Wisconsin River outside Avoca, she attended the first half of 7th. grade in Mineral Point and the rest of that year in Avoca. The next fall after one week in 8th. grade, because she was so far ahead of the other students, they moved her ahead into the freshman year of high school.

Mother was the youngest of five children. Anne, the oldest girl, was a little mother to the three younger sisters, Berniece, Alice, and Laura. Alice was two years older than Mother, but they were close companions throughout their lives. I’ve featured three of these sisters in my four book O’Shaughnessy Chronicles. Mother is Catherine and her sisters, Anne and Alice, are Sharon and Ruby in those stories.

Alice was the confident, dominant, and resourceful older sister. Mother was the subservient, romantic dreamer. Whereas Alice reached the pinnacle of success in her career as a head nurse, Mother was never quite as successful. She became a competent teacher and state employee, but was never able to pursue her dream of becoming a librarian and a published poet.

I explored and chronicled this sisterly relationship throughout the O’Shaughnessy series, although primarily in the third O’Shaughnessy book, Puppet on a String.

Mother told about the love of her life, Carl Spencer, in a memoir she wrote when she was ninety-three years old. Carl becomes the dashing Jonathon Hays in my stories. But Mother’s and Carl’s relationship didn’t endure, and she married my father, Harold Thorpe.

Harold was a renowned athlete in his hometown, Stoughton, Wisconsin, and throughout southern Wisconsin. He continued playing football and baseball after high school, even having an opportunity to join the Green Bay Packers as a punter and fullback. But those were lean years when Packer players relied on income from passing the hat, so he attended Ripon College to play football there. He was President of his 1933 Ripon College class.

After almost dieing in a car accident, he could no longer play football, so he dropped out of college and began a career as a produce manager in a Madison grocery store, the place where Mother met him. Mostly recovered from the accident, he played baseball for Madison Home Talent baseball teams, pitching several no hitters in the process.

Mother was a scholar, a writer, and loved music, but she didn’t know a football from a baseball—and wasn’t much interested in learning or joining my father in after-game celebrations. They were never a match and divorced when I was eleven years old. She never remarried.

I followed in my father’s footsteps when in high school, earning eleven varsity letters during those four years. But, only twice, did Mother participate in my first-love of those days. The first time she became involved, soon after the divorce, I was moping around complaining that I had no one to play ball with. She said, “Okay, I’ll play catch with you.” I showed her how to wear a glove, walked twenty paces away, turned, and threw the ball. It hit her between the eyes and decked her on the spot. I thought I’d killed her. I never again asked her to play catch—and she never volunteered.

Of the dozens of competitions I played over four years, Mother only attended one high school game. I scored forty-five points that night on the basketball court, twice as many as my year-long average. I fouled out with four minutes left in the game; therefore I walked alone to the bench. She was far more impressed by the ovation I received than the points I scored.

I never expected her to attend games or resented her absences because I knew the long hours she worked to maintain our home, the many hours she labored so I could spend time studying and playing games. And although she desperately needed more help at home, she never urged me to give up my passions. Deep down, I’m sure she understood that the coaches were now my father-figures and my time studying would help achieve her dream for me. But she paid a price that I never fully appreciated as a youth.

Dad and Mother had married during the depression years when work was scarce, so while looking for employment or being transferred from one work location to another, we spent most of my early years moving from Wisconsin to Colorado, then to New Mexico, and from there to California, back to Wisconsin, then to California again before returning to Wisconsin one last time—sometimes far from her beloved family members.

Mother returned to her childhood home, Mineral Point, after the divorce. With few resources and little income, she, at first, relied on her mother’s assistance. We lived in a tiny house on South Wisconsin Street in Mineral Point, a house that her mother, Elizabeth Fitzsimons, had purchased.

I described Mother’s difficult first days after the divorce in Chapter One, “Love is in the Doing,” of my book, America’s Small Town Heroes, because I feel her actions perfectly illustrate the love as doing concept. I wrote:

“With very little income and no cash reserves, my mother was forced to work at menial labor. She stoked the coal furnace at five o’clock each morning so the house would be warm when I got out of bed. Having washed all my clothes in a wringer washer and hung them out to dry on the weekend; she placed the day’s selection over the foot of my bed ready for me to jump into when I awoke. By the time I got up she had breakfast on the table, although she had already departed for work with no time to eat any herself. She walked ten blocks to the Burgess Battery factory where she stuffed carbon into hundreds of little cylinders all day long. I’ll never forget her coming home each night – her first job to refuel the furnace. She was so black with carbon from head to foot that she couldn’t be seen in the coal bin. After heating the water and cleaning herself up – we had no hot water or indoor plumbing – she cooked supper, and later cleared the table and washed the dishes in another pan of stove-boiled water. Then she or Grandmother Fitzsimons, when she was with us, helped me with my homework before going to bed.”

During those first years after the divorce she attended summer and night classes and sometimes she took correspondence courses, all towards achieving the degree she needed to return to country school teaching. After four years she succeeded and she signed a contract for her first school outside Barneveld, Wisconsin. She taught country schools for several years, and then she returned to the Department of Motor Vehicles job that she’d held prior to marriage. She continued working at the Madison Department of Motor Vehicles until her retirement.

Through all life’s difficulties she encouraged me to strive for better things—to achieve an education and become a life-long learner. She was a life-long learner herself, always following the national news and frequently reading about world events. And she remained a teacher all her life, making sure that I knew all that she knew.

Mother loved music but was never able to take the lessons required to learn an instrument. She had no money for lessons when she was young and didn’t have the time for lessons as an adult, although money was scarce then, too. So she did what was possible; she learned to play the piano by ear. She could hear a song that she liked, tinker with it for awhile, and then pound it out on the piano keys like an accomplished musician. My Uncle Earl, Anne’s husband, said she could get more music out of a piano than anyone he knew who played from notes.

I love music, too. But unfortunately for me, that’s a skill I was never able to master. She tried her hardest to teach me to sing and play an instrument, but I’m more tone-deaf than a dead man in the coffin, so the best I can do is listen to music on the radio.

I love music, too. But unfortunately for me, that’s a skill I was never able to master. She tried her hardest to teach me to sing and play an instrument, but I’m more tone-deaf than a dead man in the coffin, so the best I can do is listen to music on the radio.

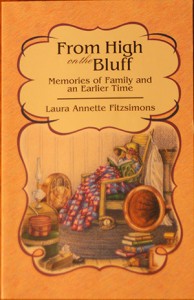

At ninety-three years of age, Mother wrote From High on the Bluff, telling about her thirty years before marriage, a life that was nothing like the vagabond and lonely years she lived thereafter.

She described in her book a young woman who was very different from the mother I knew. She’d lived her first thirty years experiencing excitement and with dreams and aspirations for a future that were unlike the one she came to know.

Although life was difficult, she remained resilient and resourceful to the end—all one-hundred-three years. Life wore her down, but she retained fond memories of her earlier years, and she frequently told me those stories. I didn’t know it then, but those memories sewed the seed for my writing career.

Although she didn’t live long enough to read the stories I’ve written, her love of literature and writing influenced me far more than she could ever know or hope for.

I could never have achieved this outcome if my mother hadn’t clung to ideals and dreams that she was never able to achieve, ideals and dreams that I’ve fictionalized with an ending I think she would have liked.