“That night at the graduation ceremony, Will and Mary sat in the front row. Will smiled his broadest, most enthusiastic smile, and when Catherine faltered on a line, he furrowed his brows, wiggled his ears, and stuck out his tongue.”—Bittersweet Harvest

In real life, my mother, Laura Annette Fitzsimons, graduated from Avoca School in rural Iowa County, Wisconsin in 1924. In my fictional O’Shaughnessy Chronicles novels, three sisters all graduate from a rural southwest Wisconsin high school between 1940 and 1943.

Today, we tend to take high school graduation for granted. About 90 percent of Wisconsin adults over the age of 25 have graduated from high school.

But for rural Wisconsin farm kids early in the twentieth century, graduating from high school was, in fact, a remarkable accomplishment.

But for rural Wisconsin farm kids early in the twentieth century, graduating from high school was, in fact, a remarkable accomplishment.

“There were eight girls and only two boys in my class, not a very good ratio. Sorry Me!” my mother jested in her 1999 memoire From High on the Bluff. “But I should have considered myself lucky. Alice had no boys in her class and only three other girls. When there was a high school dance, they held the dance at City Hall and invited everyone else from town to come too, or there wouldn’t have been anyone to dance with.”

Early in the twentieth century, most Wisconsin teens only finished the eighth grade, even though there had long been high schools in the state. The first high school graduating class in Wisconsin was in Racine in 1857. Later, in the 1870s, state law allowed for the establishment and funding of Wisconsin’s first free high schools. Here in Iowa County, Mineral Point’s first free high school opened in 1875. By 1917, more than 300 high schools dotted the state.

But early in the twentieth century, teens who lived in cities like Milwaukee were more likely to graduate from high school than their rural counterparts. In 1921, the state of Wisconsin set out to improve graduation rates for rural kids, with the creation of union high school districts in rural areas. Freshmen in union high school districts funneled in from surrounding, rural K-8 districts.

Today, most Wisconsin school districts serve students in grades kindergarten through twelve. But in a century-old remnant from the 1921 state law, there remain in Wisconsin ten rural, high school-only union districts. Today, the Wisconsin Union High School System includes Arrowhead, Big Foot, Central/Westosha, Hartford, Lake Geneva, Lakeland, Nicolet, Union Grove, and Waterford.

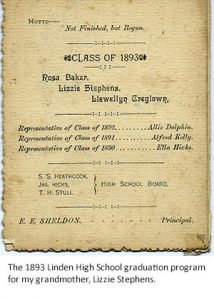

Although high school attendance and graduation rates increased in my mother’s era – during her parents’ generation here in Iowa County, Avoca had zero graduates in 1902, Mineral Point, nineteen, and Linden, four – those rates remained stubbornly low in the first decades of the twentieth century. In 1920, only about half of Wisconsin rural school children who finished the eighth grade went on to high school. And only about half of those ultimately graduated with a four-year high school diploma.

But mindsets were shifting.

“There is coming to be a feeling and a belief that all children who are capable of receiving such instruction should have high school training,” wrote C.P. Cary, state superintendent of schools, in 1919. “A democracy in order to be safe must see to it that the rank and file of the people have much more education than can be obtained by the time the child is fourteen.”

“In steadily increasing measure, high school matriculation and graduation are becoming the goals of Wisconsin school pupils,” Joseph Schaefer, superintendent of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, wrote in a Wisconsin Magazine of History article in 1926. “The time appears to be at hand when all who enter the first grade will be expected to complete the twelfth.

Raising the rate of high school graduates, Schaefer continued, “has a social significance too great to be lightly considered.”

By the Great Depression, most Wisconsin teens were giving high school a try.

Still, as students got older, they tended to drop away. In 1930, 98 percent of Wisconsin children ages 7 to 13 were enrolled in school. Attendance dropped off sharply, however, to 86 percent of 14 and 15 year olds, and 63 percent of 16 and 17 year olds. Many teens in this era went to some high school, but never graduated.

By the 1940s, several decades of educational policy shifts, and growing public sentiment in favor of finishing high school, were having a clear impact. State law changes had increased funding for school buses for rural children, and since the 1920s state law had required children through age 16 to remain in high school. (As an alternative, they could transfer to vocational school at 14. Later, in the 1960s, the state’s compulsory school age was raised to 18, with 16-year-olds allowed to transfer to vocational school).

Wisconsin’s high school graduation rate rose steadily through mid-century, although it continued to lag behind the national average. In 1940, 13 percent of Wisconsin adults over age 25 had finished high school, compared to the national average of 24 percent. In 1950 – five years before I graduated from Barneveld High School in 1955 – U.S. Census records show that about twenty percent of Wisconsin adults over age 25 had graduated from high school, compared to the national average of 34 percent. And by 1960, 26 percent of Wisconsin adults over age 25 had finished high school, compared to 41 percent nationally.

Eventually, Wisconsin caught up – and exceeded – the national average. Today, about 90 percent of Wisconsin adults over the age of 25 have finished high school, compared to about 80 percent nationally.

More than a century and a half after the first free high schools opened in Wisconsin, nearly all of the adults who live in the state have finished high school. That’s a great tribute to those who had the foresight to create high schools in the nineteenth century, and to continue to improve them in the twentieth century.

One can only imagine, with advances in technology and other modern machinations, what high school will look like for my four grandchildren – and their grandchildren – as schools plunge ahead into the twenty-first century.